PETITION: Stop Prolonging Fossil Fuels and Promoting False Solutions, that Threaten Environmental and Community Safety, and the Human Rights Violations

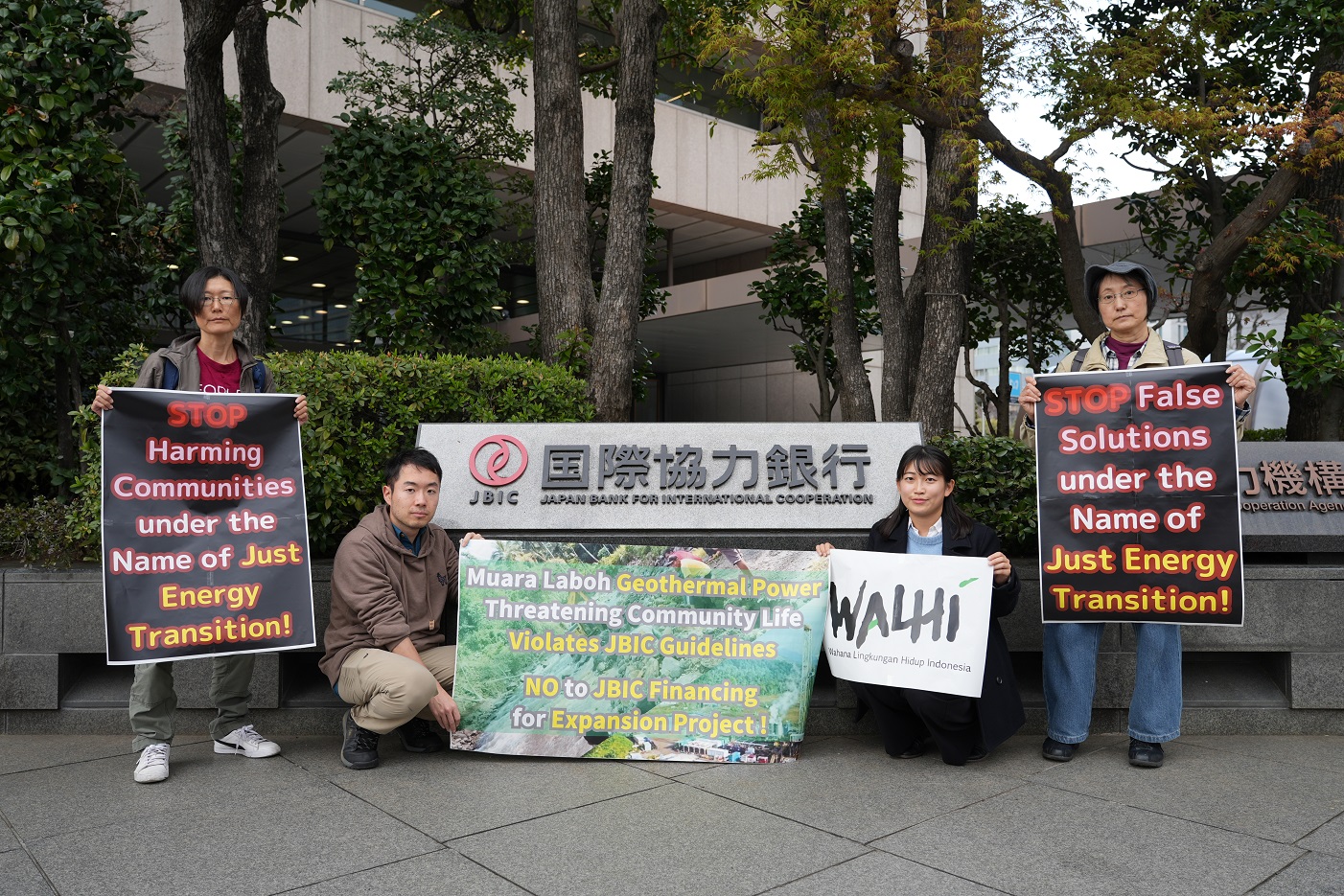

The 2nd Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) Ministerial Meeting is being held in Indonesia from August 20 to 21. Indonesian civil society organizations, including the Indonesian Forum for the Environment) (WALHI/FoE Indonesia), took action in front of the Japanese Embassy on the first day of the Ministerial Meeting and submitted a petition (signified by 41 organizations) to call on the Japanese government to stop prolonging fossil fuels and promoting false solutions that threaten environmental and community safety, and the human rights violations through AZEC and instead support a rapid, fair and equitable decarbonization and energy transition in a way that ensures the meaningful participation of local communities and civil society groups in Indonesia.

Below is the petition submitted by Indonesian civil society organizations to the Japanese government (English translation).

*) This English version is an interpretation of the original Indonesian version. If there are any differences in words or sentences, please refer to the Indonesian version.

August 20, 2024

Mr. Joko Widodo, President of Indonesia

Mr. Kishida Fumio, Prime Minister of Japan

PETITION: Stop Prolonging Fossil Fuels and Promoting False Solutions, that Threaten Environmental and Community Safety, and the Human RIghts Violations

We, the undersigned, are Indonesian civil society organizations engaged in climate, environmental protection, human rights, and energy. We express our deep concern over the Asia Zero Emission Community (AZEC) initiative led by Japan under the Green Transformation (GX) strategy, which is intended for implementation in Indonesia.

Although this initiative presents itself as part of the efforts towards carbon neutrality through broad partnerships, we see it as a greenwashing effort masquerading as decarbonization. The initiative is likely to further enrich already profitable corporations while spreading “false climate solutions" in Indonesia, leading to additional human rights violations against indigenous peoples and local communities. AZEC, lacking meaningful participation from local communities and Indonesian civil society organizations, will impede a swift, just, and equitable energy transition.

We call on the governments of Japan and Indonesia to cancel the AZEC initiative, which extends the use of fossil fuels, relies on false solutions that threaten environmental and community safety, and leads to human rights violations. We also urge the Japanese and Indonesian governments to collaborate and support a rapid, just, and equitable energy transition/decarbonization that ensures meaningful participation from local communities and civil society groups in Indonesia.

Our appeal is based on the reality that AZEC will only create problems for democracy, the environment, and communities in Indonesia. This initiative lacks transparency, openness of information, and meaningful public participation; it extends the use of fossil fuels; introduces false solutions that threaten environmental and community safety; and may lead to further land grabbing and deforestation in Indonesia, as well as creating debt trap risk for the country. We will elaborate on these points below:

(1) The Implementation of AZEC in Indonesia Violates Democratic Rights by Failing to Provide Transparency, Access to Information, and Meaningful Participation for Local Communities and Civil Society Groups

The projects, agreements, and collaborations under the AZEC initiative may have significant impacts on the lives of people in Indonesia. However, the decisions to greenlight these projects, agreements, and collaborations outlined in the AZEC documents have never been openly consulted with local communities and civil society groups in Indonesia.

As an initiative claiming to be part of climate action and decarbonization efforts, AZEC fails to adhere to the principles of public participation in climate action as mandated by Article 12 of the Paris Agreement. This article requires all ratifying countries to enhance climate change education, training, public awareness, public participation, and public access to information, recognizing the importance of these measures in responding to climate change.

The transparency issues within the AZEC projects are evident in the Legok Nangka Waste-to-Energy (WTE) project in West Java, which is also included in the AZEC documentation. The Legok Nangka WTE project could burden and harm the country’s finances with a $100 million loan from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), part of the World Bank. A total of 100 million US dollars has been allocated, with part of it designated for the Legok Nangka WTE project. Additionally, the central and regional governments are burdened with a tipping fee of 386,000 rupiahs per ton of waste processed. The selection of incinerator technology for this project is to have been influenced by technical assistance from the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA), which ultimately led to the Sumitomo-Hitachi Zosen consortium—a Japanese company that sells incinerators globally—winning the bid. The substantial tipping fees from this project will benefit Japanese stakeholders but disadvantage the public, who will bear the cost through taxes[1].

The lack of meaningful participation from local communities is also evident in the Muara Laboh geothermal project (PLTP) in West Sumatra, which has received investment from INPEX and Sumitomo Corporation. Phase 1 of the Muara Laboh PLTP was funded by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI), and Phase 2 is currently under consideration for support from JBIC and NEXI. This project was identified by Airlangga Hartarto, Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs, as a priority within AZEC. However, the local community surrounding the Muara Laboh geothermal project reports that since the project’s inception in Phase 1, the company has not transparently communicated potential impacts to the community, appearing to withhold much of the information that should have been disclosed. Public outreach was not conducted involving directly affected communities but was instead done through community leaders and traditional authorities. WALHI also received reports that land acquisition processes between 2010-2016 involved pressure and intimidation on affected communities to accept the project, with local officials and thugs forcing landowners to relinquish their lands to intermediaries, who then dealt directly with the company on land settlement matters.[2].

Japanese financial institutions and organizations, which are currently key drivers of AZEC, also have a poor track record regarding transparency and meaningful participation from local communities where their projects are implemented. The Tangguh LNG project in West Papua, supported by JBIC and NEXI (with investments from Mitsubishi Corporation, JX Nippon Oil & Gas Exploration, Sojitz Corporation, Sumitomo Corporation, INPEX, Mitsui & Co, JOGMEG and Kansai Electric Power Company as LNG buyers), was operated without meaningful consultation and participation. The Environmental Impact Analysis (AMDAL), for instance, was conducted without the participation of local communities. As a result, ecologically important areas for the community (coastal areas and mangrove forests) were damaged, and their activities were restricted (fishing areas near the gas platform). The project also forcibly displaced three tribes (Sowai, Wayuri, and Simuna) from the land of the Sumuri indigenous people, the traditional landowners in the area, leading to the loss of access to their traditional farming and hunting grounds[3].

The general public in Indonesia has not received adequate information about the projects, agreements, and commitments to be undertaken by the Japanese and Indonesian governments through AZEC, and some official information provided by the Indonesian government has raised suspicions of information manipulation. One example of potential information manipulation is seen in the press release from the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs dated December 18, 2023. The release mentioned three priority projects in the energy transition under the AZEC framework: the construction of the Geothermal Power Plant in Muara Laboh, the Waste-to-Energy Plant in Legok Nangka, and the management of peatland for food commodities in Central Kalimantan[4].

However, the official website of Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) only confirmed the signing of cooperation agreements for two projects: the amendment of the Power Purchase Agreement for the Geothermal Power Plant in Muara Laboh and the preliminary understanding document for the Waste-to-Energy Plant in Legok Nangka[5]. There is no official statement from the Japanese government indicating any cooperation on peatland management for food commodities in Central Kalimantan. The only peatland management project in Central Kalimantan documented in the AZEC Progress Report is a “Study on Stock-Based Peatland Water Management Technology for Stable Wood Biomass Supply." The lack of clear information raises uncertainty about whether the “peatland management for food commodities in Central Kalimantan," as mentioned on the Coordinating Ministry for Economic Affairs’ website, is the same as the “Stock-Based Peatland Water Management Technology for Stable Wood Biomass Supply Study" described in the Progress Report.

Therefore, the implementation of AZEC in Indonesia effectively undermines democratic rights in the country. The execution of projects, agreements, and collaborations within AZEC is carried out without considering the aspirations of the people and without creating space for meaningful participation from civil society groups. Additionally, the governments of Indonesia and Japan have failed to account for the potential social, environmental, and human rights impacts that could affect the broader community as a result of AZEC’s implementation in Indonesia. For these reasons, the application of AZEC must be halted, as it does not serve the interests of the people.

(2) Promoting technologies that extend the use of fossil fuels within AZEC will not address the climate crisis but will instead prolong the suffering of the people

The various projects, agreements, and collaborations within AZEC planned for implementation in Indonesia openly promote approaches and technologies that could extend the use of fossil fuels. These approaches and technologies include hydrogen, ammonia, bioenergy, carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), gas, and LNG. Such approaches and technologies cannot be expected to contribute significantly to the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions necessary to meet the 1.5°C target of the Paris Agreement, and therefore, do not aid in combating climate change. Additionally, some of these technologies remain unproven, immature, and extremely costly.

The Japanese government’s continued promotion of approaches and technologies that could extend the use of fossil fuels is evident in a project where JICA tasked Japanese companies—TEPCO Power Grid, Inc. (TEPCO PG), Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc. (TEPCO HD), JERA Co., Inc. (JERA), and Tokyo Electric Power Services Co., Ltd. (TEPSCO)—to complete the “Electric Power Sector Data Collection Survey in Indonesia for Decarbonization" in March 2022[6]. The roadmap for achieving carbon neutrality by 2060, as outlined in this survey, proposes prioritizing ammonia and biomass co-firing in existing coal-fired power plants and positioning ammonia, hydrogen, and LNG (with CCS) as primary fuels in the long term.

Recently, JICA also planned to implement a “Master Plan for the Energy Transition Management Project in Indonesia" over two years, extending until October 2025. A review of the agreement details with Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) reveals recurring mentions of CC(U)S, hydrogen, ammonia, biomass, and LNG[7].

Efforts to extend the use of fossil fuels in Indonesia pose significant threats to the environment and communities. For example, the Japanese company Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, Ltd. (MHI) has proposed advancing co-firing at several power plants: Suralaya in Banten, Paiton in East Java, and Muara Karang in Jakarta. However, these power plants have ongoing environmental issues and safety threats to local communities.

The Suralaya power plant, operational since 1984, has been highlighted in a CREA (2023) report for its negative impacts on public health and the economy. The report notes that it contributes to the loss of 1,470 lives annually and incurs health-related costs amounting to USD 1.04 billion[8].

The Paiton power plant complex is reported to produce the largest amount of hazardous waste (B3) in East Java, totaling 153 million tons per year, which represents 80% of the region’s annual total production of 170 million tons[9].

The Muara Karang gas-fired power plant (PLTGU) is reported to have significant estimated impacts on public health. Specifically, the health cases associated with the plant are as follows: PLTGU Block 1 has approximately 725,760 cases per year, PLTGU Block 2 has about 312,768 cases per year, and the relatively new PLTGU Block 3 reports 759,035 cases per year[10].

The Japanese government is also continuing efforts to develop new gas fields in Indonesia. The proposed development of the Abadi LNG (Masela field) and CCS is being promoted by INPEX CORPORATION offshore in Maluku Barat Daya. However, recent reports by the International Energy Agency (IEA) have reaffirmed that to meet the Paris Agreement targets, “no new oil and gas fields should be explored from now on.[11]" Despite INPEX aiming for a Final Investment Decision (FID) by the end of the 2020s and production in the early 2030s, this new gas development plan is clearly contrary to global climate action and should therefore be halted immediately.

The implementation of other technologies such as CCS (carbon capture and storage) will also not address emissions problems in fossil fuel projects and could result in prolonged impacts on local communities. The IEA has questioned the track record of CCS, noting that “the history of CCUS has largely been one of unfulfilled hopes.” In Indonesia, the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources (ESDM) has announced at least 16 CCS/CCUS projects, including new gas projects like the Masela Block. President Jokowi has also issued Presidential Regulation No. 14 of 2024 on Carbon Capture and Storage Activities, which will provide additional incentives for the fossil fuel industry to adopt this technology and allow the import of carbon from abroad for injection in Indonesia. The practice of transferring carbon from one country to another, such as Chubu Electric’s plan to export CO2 from Japan to CO2 storage in the Tangguh gas fields in Papua[12], is nothing more than a new form of waste colonialism.

One of the locations where a CCUS project listed under AZEC is planned to be implemented is the Sukowati oil field in East Java. This field has experienced multiple explosions, accidents, and gas leaks, posing threats to the surrounding communities. On July 29, 2006, a massive explosion occurred at the Sukowati Pad A well. Following the incident, dozens of people were hospitalized after inhaling harmful gas released with the explosion, resulting in dizziness, nausea, vomiting, and fainting. Thousands of residents around the well had to evacuate, and due to the trauma and distant evacuation sites, hundreds of students were unable to attend school. On January 21, 2008, an explosion at the Sukowati Pad B well injured three workers with burns and broken bones, causing some schools to halt classes and send students home. On December 2, 2008, a gas leak at the Sukowati Pad A Well 9 released unpleasant-smelling gas, leading to respiratory distress, headaches, nausea, and vomiting. At that time, hundreds of residents from Ngampel and Sambiroto villages in Kapas District, Bojonegoro, fled their homes in search of safe evacuation places.[13].

The promotion of technologies that extend the use of fossil fuels, such as Hydrogen, Ammonia, Bioenergy, CCS/CCUS, Gas, and LNG, under AZEC will only prolong the suffering of the people, as outlined above. Therefore, the governments of Indonesia and Japan must halt such initiatives under AZEC to ensure that environmental and community safety is protected and prioritized.

(3) AZEC promotes false solutions that pose threats to environmental safety and community well-being, as well as leading to human rights violations

The various approaches and technologies promoted through AZEC, presented as part of decarbonization efforts, in reality, pose threats to environmental integrity and human rights in Indonesia. For us, climate action projects that fail to consider potential environmental damage and threats to community safety are merely false climate solutions.

One such project supported by AZEC for implementation in Indonesia is the Geothermal Energy project. In Indonesia, the regulatory framework for geothermal energy post-UU Cipta Kerja remains exploitative, potentially exacerbating agrarian conflicts and increasing risks of criminalization against local communities. Moreover, findings from geothermal activities indicate correlations with seismic risks, land subsidence, landscape changes, ecosystem damage, pollution, and ongoing greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, geothermal projects in Indonesia often threaten land access and criminalize local communities.

For example, the Muara Laboh Geothermal Power Plant (PLTP) Phase 1 in Solok Selatan, West Sumatra, has had severe impacts on farmers who rely on river flows in the area. Many farmers near the project site have experienced failed rice crops due to irrigation water carrying heavy black material, which has hardened the soil and rendered the farmland unusable. The PLTP Muara Laboh also poses high risks of environmental contamination and impacts on local communities, as agricultural and residential areas are situated just 250-500 meters from mining and power plant activities[14].

Other problems with geothermal projects in Indonesia have emerged, such as with the Sarulla and Sorik Marapi Geothermal Power Plants in North Sumatra. The Sarulla PLTP (invested in by ITOCHU Corporation, Kyushu Electric Power, and INPEX, and financed by JBIC) is one of the geothermal projects mentioned in the AZEC progress report. It has caused a drastic decline in farmers’ incomes due to crop damage, water channel destruction, and unfair land acquisition that disregarded the value of residents’ crops[15]. Meanwhile, the Sorik Marapi PLTP in Mandailing Natal Regency exemplifies how geothermal operations can pose serious threats to local communities. The Sorik Marapi PLTP has repeatedly experienced explosions and gas leaks, causing hundreds of people to be poisoned and even resulting in fatalities. On January 25, 2021, dozens of people fainted and were rushed to the hospital, five of whom—two of them toddlers—eventually died, likely from inhaling toxic gases leaking from the geothermal drilling well. Unfortunately, these leaks have continued, repeatedly causing serious harm to hundreds of people[16].

In Mataloko, Ngada Regency, East Nusa Tenggara, the geothermal project has caused steam and mud eruptions since 2006. Various local crops in Mataloko, such as avocados, candlenuts, coffee, cloves, pumpkins, and timber plants, have suffered damage following these eruptions. The eruptions in Mataloko have also led to health impacts in the community, including respiratory infections and skin rashes[17].

Geothermal activities in Indonesia have also sparked conflicts and resistance in various regions, such as the geothermal projects in Padarincang in Banten, Gede-Pangrango and Ciremai in West Java, Baturaden and Dieng in Central Java, Arjuno-Welirang and Lemongan in East Java, and Wae Sano and Poco Leok in East Nusa Tenggara. Given the strong public opposition, social and ecological impacts, and resulting conflicts from geothermal project development in Indonesia, these projects should not continue under AZEC or any other initiatives in the name of energy transition or decarbonization.

Another false solution in AZEC is the Waste-to-Energy (WTE) project, one of which will operate in Legok Nangka, West Java. We have previously voiced our strong criticism of the use of incinerators in the Legok Nangka WTE project[18]. Incinerators in WTE projects will merely replicate waste-burning models and continue to release significant greenhouse gas emissions. Incinerators burn a mix of waste, including organic and plastic waste made from fossil fuels. Recent studies have shown that incinerators in the United States[19], the United Kingdom[20], and Europe[21] emit more greenhouse gasses than coal-fired power plants. Burning organic waste only converts methane emissions from organic waste into CO2 on a massive scale, further distancing Indonesia from its Paris Agreement targets and the Global Methane Pledge[22], which Indonesia recently signed.

Another aspect of the false solutions supported by AZEC includes the need for critical minerals for battery storage technologies and electric vehicle ecosystems. The AZEC Joint Statement and Chairman’s Summary from March 2023 highlight the importance of developing critical mineral supply chains. While the specific details of agreements within the AZEC initiative are not yet clear, they warrant significant attention, especially given Indonesia’s status as the world’s largest nickel reserve, with increasing demand driven by battery needs.

The contradictions become evident in areas where nickel and other critical minerals are extracted as part of efforts towards a decarbonized society. These areas often face deforestation of carbon-absorbing forests and continued or increased greenhouse gas emissions from existing coal and gas power plants used to fuel critical mineral industries in Indonesia.

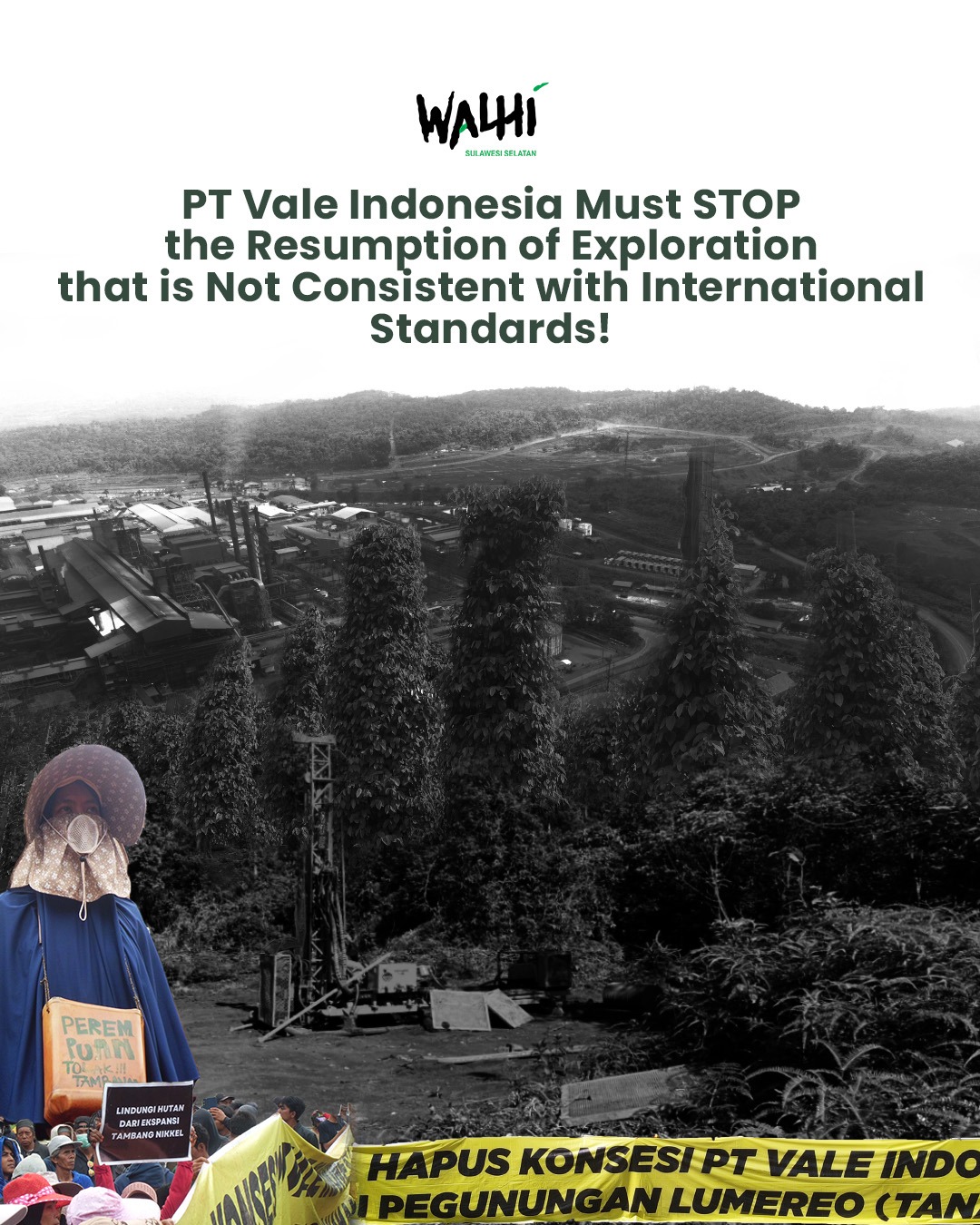

Furthermore, behind the narrative of critical mineral development promoted as essential for decarbonization, it is crucial to ensure full recognition, protection, and fulfillment of human rights for indigenous and local communities living in these areas, especially their right to say “No” and reject mining projects to safeguard their living spaces and rights. Reports of serious human rights violations, including the deployment of Indonesian military and fully armed police officers against local communities in Sulawesi protesting the expansion of the Tanamalia block of the Sorowako Nickel Mining Project, invested by a Japanese company, have already surfaced.

The various approaches or technologies promoted within AZEC are part of what we call false solutions. These approaches and technologies are claimed to help reduce greenhouse gas emissions and combat climate change. However, in reality, they are ineffective, do not significantly reduce emissions, and have long-term negative impacts, worsening environmental quality and posing threats to human safety, human rights violations, and declining quality of life for vulnerable groups, such as women, people with disabilities, children, and the elderly, who already bear the heavier burden of climate change impacts. Given the numerous problems caused by the implementation of false solutions by AZEC on the environment and communities, the Japanese and Indonesian governments should halt AZEC projects that pose such threats.

(4) AZEC supports projects that may lead to land and sea space grabs and further deforestation in Indonesia. The initiative’s promotion of certain projects has been linked to significant environmental and social issues

The projects, agreements, and collaborations supported by AZEC often require extensive land use, leading to land grabs and further deforestation in Indonesia.

The AZEC initiative in Indonesia, for example, includes cooperation to facilitate the development of the new capital city, as outlined in the Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) signed by JBIC and the Indonesian National Capital Authority in May 2023[23], which was also included in the AZEC MoU list in December 2023[24]. We are concerned that JICA[25], which has been conducting studies since 2022 to gather and verify information about the new capital city (Nusantara/IKN), has never provided opportunities for local communities and civil society groups in Indonesia to participate, nor has it adequately listened to their voices and concerns.

The voices and concerns of local communities and civil society groups in Indonesia are evident in a report by the East Kalimantan Indigenous Peoples Alliance (AMAN), which notes that of the total IKN area of 252,204 hectares, 235,667 hectares are indigenous lands that must be sacrificed for IKN. The report also mentions that since the designation of the IKN location in indigenous lands controlled by Industrial Forest Plantation (HTI) companies, indigenous peoples have faced intimidation by these companies, and their access to their lands has been prohibited under threats of arrest and imprisonment, leaving them unable to cultivate their fields and lacking sustainable livelihood solutions. Meanwhile, HTI license holders have expanded their permits, further encroaching on indigenous lands and depriving them of access to forests they once managed sustainably.[26].

In the development of IKN, land grabs extended not only to terrestrial areas but also to marine spaces, as evidenced by efforts to marginalize traditional fishermen from their ancestral waters. The Indonesian Law No. 3 of 2022 regarding the State Capital (IKN) and the East Kalimantan Zoning Regulation do not recognize the coastal communities, particularly fishermen, as stakeholders in the management of the Balikpapan Bay. Moreover, the East Kalimantan Zoning Regulation does not allocate residential areas for fishermen in Balikpapan Bay. These regulations also fail to prioritize the protection of the 16,800-hectare mangrove forest in Balikpapan Bay from damage caused by IKN development and the surrounding extractive industries. It is estimated that at least 10,000 fishing families in Balikpapan Bay will be affected by the loss of their marine space due to the IKN development[27].

AZEC also recognizes the existence of REDD projects in Indonesia through the Joint Crediting Mechanism (JCM). In our view, REDD projects are clearly part of climate change false solutions and contribute to land grabbing. REDD projects, as part of carbon trading, are based on a fundamentally flawed assumption that the climate crisis is solely caused by carbon, allowing emissions from one source to be offset by reductions from another. This flawed assumption also underpins the rationale for assigning conservation efforts to corporations rather than recognizing the role and capacity of indigenous peoples and local communities who have traditionally managed forests. The accumulation of land with claims of climate action by promoters of REDD+ and similar schemes is estimated to have resulted in the loss of 2.6 million hectares of land owned by indigenous peoples and local communities in Indonesia[28].

The Katingan project in Central Kalimantan, one of the largest REDD projects in the world, exemplifies how REDD projects can lead to land grabbing and fail to effectively protect forest areas. Since 2013, this project has received a Forest Utilization Permit for Ecosystem Restoration (IUPHHK-RE) covering 100,000 hectares for the Katingan Peat Restoration and Conservation Project, later expanding to 500,000 hectares under the same permit. The project is conducted on land seized from indigenous peoples and local communities. In 2014, the governor of Central Kalimantan agreed to allow each Dayak family to manage five hectares of contested land, but the exact location of this land was not agreed upon. Approximately 40,000 people living in 34 villages around the Katingan project area have been displaced. Additionally, persistent forest and land fires within the project’s concession areas highlight the failure of project managers to protect the region[29].

The REDD+ project known as “Hutan Harapan" in Jambi is another example of land grabbing and failed forest protection. This project received an Ecosystem Restoration permit covering 46,385 hectares. However, it has been reported to displace the traditional lands of the Anak Dalam tribe and areas designated for transmigration. Instead of halting deforestation and degradation, the REDD+ project has led to further damage, including the construction of a 26-kilometer long, 60-meter wide coal mining road. This has threatened the extinction of 1,300 plant species and 620 animal species in the Hutan Harapan ecosystem. Additionally, secondary forest timber worth over IDR 400 billion has been lost[30].

Other AZEC projects, such as the “The study of stock-based peatland water management technology for a stable supply of woody biomass" (Sumitomo Forestry), have the potential to repeat the same mistakes as the One Million Hectare Peatland Project (PLG) from the New Order era, and the food estate projects during Joko Widodo’s administration. These projects transformed peatland ecosystems into destructive monoculture plantations, infringing on the rights of indigenous peoples and local communities and causing environmental disasters. The AZEC project is planned for development on former PLG areas, which have already suffered from significant damage. This includes the loss and threat to high biodiversity such as Ramin wood (Gonystylus bancanus) and Meranti Rawa (Shorea balangeran), endemic species in the peatland region, the destruction of orangutan habitats, and the creation of primary and secondary canals stretching hundreds of thousands of kilometers. These canals have led to peatland dryness and are sources of peatland fire disasters in Central Kalimantan, releasing greenhouse gases that affect neighboring countries. Forest fires have also had serious health implications, including increased respiratory infections and premature deaths. The attempt to make this area a wood biomass supplier will further encourage the expansion of monoculture plantations. Development in former PLG areas is feared to violate spatial planning and other policies due to their location in forest and peatland protection zones. This has led to increased land conflicts, land grabbing from indigenous peoples, and the destruction of traditional agricultural and fishing systems, along with the loss of traditional knowledge and local wisdom developed by indigenous communities[31].

The approach of AZEC, which continues to allow the extension of fossil fuel use in Indonesia and the fulfillment of critical mineral supply chains, also poses a significant threat of further forest destruction and deforestation in Indonesia. Extending the use of fossil fuels will drive further coal and gas mining, leading to more forest areas being opened up. In Indonesia, nearly 5 million hectares of land have already been converted to coal mining areas, with almost 2 million hectares within forested areas. According to the Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, coal production in Indonesia is expected to continue increasing year by year (2021: 609 million tons; 2022: 618 million tons; 2023: 625 million tons; 2024: 628 million tons[32]). Additionally, the massive expansion of the nickel industry is causing deforestation in various regions of Indonesia. By the end of 2023, at least 200,000 hectares of forest land in Indonesia have been deforested due to the expansion of the nickel industry[33].

(5) AZEC Increases the Risk of Debt Distress

The AZEC scheme, which involves loans, will exacerbate Indonesia’s already poor fiscal condition. This is evident from the country’s mismanagement of debt and its precarious debt ratio. Indonesia’s debt-to-revenue ratio has significantly increased, with debt rising from IDR 2,609 trillion in 2014 to IDR 8,850 trillion in 2024, while national revenue increased from IDR 1,550 trillion in 2014 to IDR 2,802 trillion in 2024[34]. As a result, the debt-to-revenue ratio has climbed from 168.27% to 315.81%, leading to unproductive debt.

The ratio of interest payments to national revenue has also grown. This year, Indonesia’s interest payments are estimated to reach IDR 497.31 trillion, a 12.7% increase from the 2023 state budget allocation. Consequently, the estimated interest-to-revenue ratio could reach 17.74%. Additionally, in 2025, the government will face maturing debt up to IDR 800 trillion, which, when including interest, could exceed IDR 1,300 trillion[35]. Compared to the government’s annual decarbonization funding claim of IDR 81 trillion[36], or just 3.5% of the state budget, the portion allocated for debt repayment is six times greater than the funding for addressing the climate crisis.

The AZEC mechanism, which also involves state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in a B-to-B scheme, such as the US$ 500 million loan guarantee from NEXI to PT PLN[37], will further increase Indonesia’s public debt. According to Indonesia’s Public Sector Debt Statistics for Q1 2024, public debt exceeds IDR 16,000 trillion[38], with contributions from corporate public debt such as that of SOEs. Given the projected slowdown in Indonesia’s economic growth to below 5%, partly due to the threat of a climate crisis, a tax ratio still below 11%, and deindustrialization, the government should exercise caution and thoroughness in accepting offers from developed countries to avoid potential debt distress, such as debt default or unfavorable debt restructuring.

Cc:

Mr. Airlangga Hartarto, Coordinating Minister for Economic Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia

Mr. Luhut Binsar Pandjaitan, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment of the Republic of Indonesia

Mr. Bahlil Lahadalia, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources of the Republic of Indonesia

Ms. Siti Nurbaya Bakar, Minister of Environment and Forestry of the Republic of Indonesia

Ms. Retno Marsudi, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia

Ms. Sri Mulyani Indrawati, Minister of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia

Mr. Agus Gumiwang Kartasasmita, Minister of Industry of the Republic of Indonesia

Mr. Sugeng Suparwoto, Chairman of Commission VII, People’s Consultative Assembly of the Republic of Indonesia

Mr. Heri Akhmadi, Ambassador of the Republic of Indonesia to Japan

Mr. Ken Saito, Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry of Japan

Ms. Yoko Kamikawa, Minister for Foreign Affairs of Japan

Mr. Shunichi Suzuki, Minister of Finance of Japan

Mr. Shintaro Ito, Minister of the Environment of Japan

Mr. Akihiko Tanaka, President of the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Mr. Nobumitsu Hayashi, Governor of the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC)

Mr. Atsuo Kuroda, Chairman and CEO of Nippon Export and Investment Insurance (NEXI)

Mr. Yasushi Masaki, Ambassador of Japan to Indonesia

Mr. Ichiro Takahara, Chairman and CEO of the Japan Organization for Metals and Energy Security (JOGMEC)

Mr. Norihiko Ishiguro, Chairman of the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO)

Mr. Tamotsu Saito, Chairman of the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO)

Signatories:

- Wahana Lingkungan Hidup Indonesia (WALHI/Friends of the Earth Indonesia)

- Aksi Ekologi & Emansipasi Rakyat (AEER)

- Center of Economic and Law Studies (CELIOS)

- Oil Change International

- 350 Indonesia

- Jaringan Advokasi Tambang (JATAM)

- Trend Asia

- Kelompok Kerja 30 (POKJA 30)

- Solidaritas Perempuan

- Arise! Indonesia

- Solidaritas Perempuan (SP) Kinasih

- Lingkar Keadilan Ruang

- Partai Hijau Indonesia

- Greenpeace Indonesia

- Koalisi Rakyat untuk Hak Atas Air (KRuHA)

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Aceh

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sumatera Utara

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sumatera Barat

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Riau

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Jambi

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Bangka Belitung

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sumatera Selatan

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Bengkulu

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Kalimantan Tengah

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Kalimantan Barat

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Kalimantan Selatan

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Kalimantan Timur

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Jakarta

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Jawa Barat

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Yogyakarta

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Jawa Tengah

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Jawa Timur

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sulawesi Tengah

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sulawesi Tenggara

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sulawesi Barat

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Sulawesi Selatan

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Maluku Utara

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Papua

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Bali

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Nusa Tenggara Barat

- Eksekutif Daerah WALHI Nusa Tenggara Timur

[1] Proyek Insinerator PLTSa Legok Nangka: Bukan Solusi Tapi Polusi. Siaran Pers Aliansi Zero Waste Indonesia (AZWI) WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/proyek-insinerator-pltsa-legok-nangka-bukan-solusi-tapi-polusi

[2] Berhenti Mempertimbangkan Dukungan Terhadap Proyek Pengembangan PLTP Muara Laboh Tahap 2 di WKP Liki Pinangawan Muara Laboh, Kabupaten Solok Selatan, Provinsi Sumatera Barat Yang Dapat

Mengakibatkan Perluasan Dampak Negatif Terhadap Lingkungan dan Komunitas Serta Melanggengkan Pelanggaran Hak Asasi Manusia. Petisi WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/uploads/buku/PETISI_PLTP_2.pdf

[3] WALHI Tuntut Jepang Akhiri Pendanaan Terhadap Proyek Gas Fosil Yang Menimbulkan Bencana dan Kerusakan. Siaran Pers WALHI (2024). https://www.walhi.or.id/walhi-tuntut-jepang-akhiri-pendanaan-terhadap-proyek-gas-fosil-yang-menimbulkan-bencana-dan-kerusakan

[4] Implementasikan Asia Zero Emission Community, Menko Airlangga Saksikan Penandatanganan Dokumen Perjanjian 3 Proyek Prioritas. Siaran Pers Kementerian Koordinator Bidang Perekonomian (2023). https://ekon.go.id/publikasi/detail/5565/implementasikan-asia-zero-emission-community-menko-airlangga-saksikan-penandatanganan-dokumen-perjanjian-3-proyek-prioritas

[5] Minister Saito Holds Meeting with H.E. Mr. Arifin Tasrif, Minister of Energy and Mineral Resources, Indonesia. Website Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (2023). https://www.meti.go.jp/english/press/2023/1219_004.html

[6] Data Collection Survey on Power Sector in Indonesia for Decarbonization. JICA (2022). https://libopac.jica.go.jp/images/report/12342481.pdf

[7] Record of Discussions For Master Plan For Energy Transition Management Project Agreed Upon Between PT PLN (Persero) of Republic of Indonesia and Japan International Cooperation Agency. JICA (2023). https://www.jica.go.jp/Resource/english/our_work/social_environmental/id/asia/southeast/indonesia/pj8nfn000000og6h-att/report_02.pdf

[8] Dampak kualitas udara kompleks PLTU Suralaya – Banten. CREA (2023). https://energyandcleanair.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/CREA_Banten-Suralaya_HIA_ID_FINAL_09_2023.pdf

[9] Komplek PLTU Paiton Sumbang Limbah Beracun Terbesar di Jatim. Kompascom (2017). https://regional.kompas.com/read/2017/05/18/11280281/komplek.pltu.paiton.sumbang.limbah.beracun.terbesar.di.jatim

[10] Estimation of Health Impacts and Externality Costs with the Robust Uniform World Model in the Muara Karang Generation Units. Kumalaningrum dkk (2023)

[11] Net Zero Roadmap A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach. International Energy Agency (2023). https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9a698da4-4002-4e53-8ef3-631d8971bf84/NetZeroRoadmap_AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5CGoalinReach-2023Update.pdf

[12] bp and Chubu Electric sign MoU to evaluate CO2 storage in Tangguh, Indonesia. Press release Chubu Electric (2023). https://www.chuden.co.jp/english/corporate/releases/pressreleases/1211821_5163.html

[13] Warga Cemaskan Gas Beracun Paska Ledakan Sumur Sukowati. Tempo (2006) https://nasional.tempo.co/read/80841/warga-cemaskan-gas-beracun-paska-ledakan-sumur-sukowati

Belasan Siswa Keracunan Gas. Liputan 6 (2008) https://www.liputan6.com/news/read/169220/belasan-siswa-keracunan-gas

Sumur Minyak Sukowati Meledak, 3 Luka. Okezone (2008) https://news.okezone.com/read/2008/01/21/1/76843/sumur-minyak-sukowati-meledak-luka

[14] Berhenti Mempertimbangkan Dukungan Terhadap Proyek Pengembangan PLTP Muara Laboh Tahap 2 di WKP Liki Pinangawan Muara Laboh, Kabupaten Solok Selatan, Provinsi Sumatera Barat Yang Dapat Mengakibatkan Perluasan Dampak Negatif Terhadap Lingkungan dan Komunitas Serta Melanggengkan Pelanggaran Hak Asasi Manusia. Petisi WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/uploads/buku/PETISI_PLTP_2.pdf

[15] PLTP Sarulla Dianggap Merugikan Warga. VIVANews (2008). https://www.viva.co.id/berita/nasional/9313-pltp-sarulla-dianggap-merugikan-warga

[16] Jatuh Korban Berulang, Mengapa Panas Bumi Sorik Marapi Terus Jalan?. Mongabay Indonesia (2024). https://www.mongabay.co.id/2024/03/16/jatuh-korban-berulang-mengapa-panas-bumi-sorik-marapi-terus-jalan/

[17] Keluhan Seputar Pembangkit Panas Bumi, Ada Omnibus Law Khawatir Perburuk Kondisi. Mongabay Indonesia (2020). https://www.mongabay.co.id/2020/09/12/keluhan-seputar-pembangkit-panas-bumi-ada-omnibus-law-khawatir-perburuk-kondisi/

[18] Proyek Insinerator PLTSa Legok Nangka: Bukan Solusi Tapi Polusi. Siaran Pers Aliansi Zero Waste Indonesia (AZWI) dan WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/proyek-insinerator-pltsa-legok-nangka-bukan-solusi-tapi-polusi

[19] Waste incinerators undermine clean energy goals. Tangri, N (2023). https://journals.plos.org/climate/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pclm.0000100&type=printable

[20] Evaluation of the climate change impacts of waste incineration in the United Kingdom. UKWIN (2018). https://ukwin.org.uk/climate/#evaluation

[21] The impact of Waste-to-Energy incineration on climate. Zero Waste Europe (2019). https://zerowasteeurope.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/zero_waste_europe_policy-briefing_the-impact-of-waste-to-energy-incineration-on-climate_en.pdf

[22] Indonesia Joined 100 Countries to Slash Gas Methane by 30% in 2030. D-Insight kata data (2021). https://dinsights.katadata.co.id/read/2021/11/03/indonesia-joined-100-countries-to-slash-gas-methane-by-30-in-2030

[23] JBIC Signs MOU with Nusantara Capital Authority of Indonesia Promoting Development of New Capital of Indonesia. JBIC (2023). https://www.jbic.go.jp/en/information/press/press-2023/0522-017787.html

[24] MOUs towards AZEC leaders meeting. Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (2023). https://www.meti.go.jp/press/2023/12/20231218004/20231218004-9.pdf

[25] インドネシア国インドネシア新首都開発にかかる情 報収集・確認調査. JICA (2022). https://www2.jica.go.jp/ja/announce/pdf/20220323_216196_1_01.pdf

[26] Catatan Akhir Tahun. AMAN Kalimantan Timur (2022). https://aman.or.id/regional-news/catatan-akhir-tahun-2022-aman-kaltim

[27] Perampasan Ruang Laut dalam Pembangunan Ibu Kota Negara. WALHI (2022). https://www.walhi.or.id/perampasan-ruang-laut-dalam-pembangunan-ibu-kota-negara

[28] Intensification of land grabbing and more concentration of land ownership in the era of “green capitalism": News from Indonesia. World Rainforest Movement (2015). https://www.wrm.org.uy/bulletin-articles/intensification-of-land-grabbing-and-more-concentration-of-land-ownership-in-the-era-of-green-capitalism-news-from-indonesia

[29] Perdagangan Karbon: Jalan Sesat Atasi Krisi Iklim. Kertas Posisi WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/uploads/buku/Kertas_Posisi_Perdagangan_Karbon_2023_rev_compressed.pdf

[30] idem

[31] Hentikan Proyek Cetak Sawah/Food Estate di Lahan Gambut di Kalimantan Tengah. Siaran Pers WALHI (2020). https://www.walhi.or.id/hentikan-proyek-cetak-sawah-food-estate-di-lahan-gambut-di-kalimantan-tengah

[32] Terdepan Di Luar Lintasan. Tinjauan Lingkungan Hidup WALHI (2023). https://www.walhi.or.id/uploads/buku/TINJAUAN_LINGKUNGAN_HIDUP_2023_2.pdf

[33] Catatan Akhir Tahun: Karut Marut Hilirisasi Nikel, Persulit Hidup Masyarakat, Lingkungan Makin Sakit. Mongabay Indonesia (2023). https://www.mongabay.co.id/2023/12/30/catatan-akhir-tahun-karut-marut-hilirisasi-nikel-persulit-hidup-masyarakat-lingkungan-makin-sakit/

[34] Nota Keuangan dan APBN 2024 dan 2019. Kemenkeu 2024. https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/informasi-publik/keuangan-negara/uu-apbn-dan-nota-keuangan

[35] Profil Jatuh Tempo Utang Direktorat Jenderal Pengelolaan Pembiayaan dan Risiko (DJPPR) Kementerian Keuangan. CNBC Indonesia 2024.https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/news/20240610063712-4-545114/utang-jokowi-tembus-rp-8338-t-4-tahun-nambah-rp-3500-t

[36]Tekan Emisi Karbon Lewat Pembiayaan Kreatif. Media Keuangan Kemenkeu 2024, https://mediakeuangan.kemenkeu.go.id/article/show/tekan-emisi-karbon-lewat-pembiayaan-kreatif

[37] Perkuat Kolaborasi dengan NEXI – Jepang, PLN Peroleh Dukungan Penjaminan Pinjaman USD500 juta. Siaran Pers PLN. https://web.pln.co.id/cms/media/siaran-pers/2023/03/perkuat-kolaborasi-dengan-nexi-jepang-pln-peroleh-dukungan-penjaminan-pinjaman-usd500-juta/

[38] Statistik Utang Sektor Publik Indonesia Triwulan I. https://www.djppr.kemenkeu.go.id/suspi