New Report on Climate Impacts of Japan's Public Finance

Read the report: Climate Impacts of Japan’s Public Finance: Greenhouse Gas Emissions from JBIC’s Fossil Fuel Finance and Alignment with the 1.5°C Goal

Summary Briefing: Japan’s Hidden Responsibility: Overseas GHG Emissions from Government-Backed Fossil Fuel Finance

FoE Japan released new research report that quantifies greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions associated with the Japan Bank for International Cooperation’s (JBIC) financing of overseas fossil fuel projects. The study delivers a project-by-project accounting of the greenhouse gases driven by JBIC’s fossil-fuel financing, testing JBIC’s trajectory against a 1.5°C pathway. The study exposes JBIC’s financed emissions as vast—comparable to some of the world’s largest emitting countries.

Key Findings

JBIC’s enormous greenhouse gas emissions

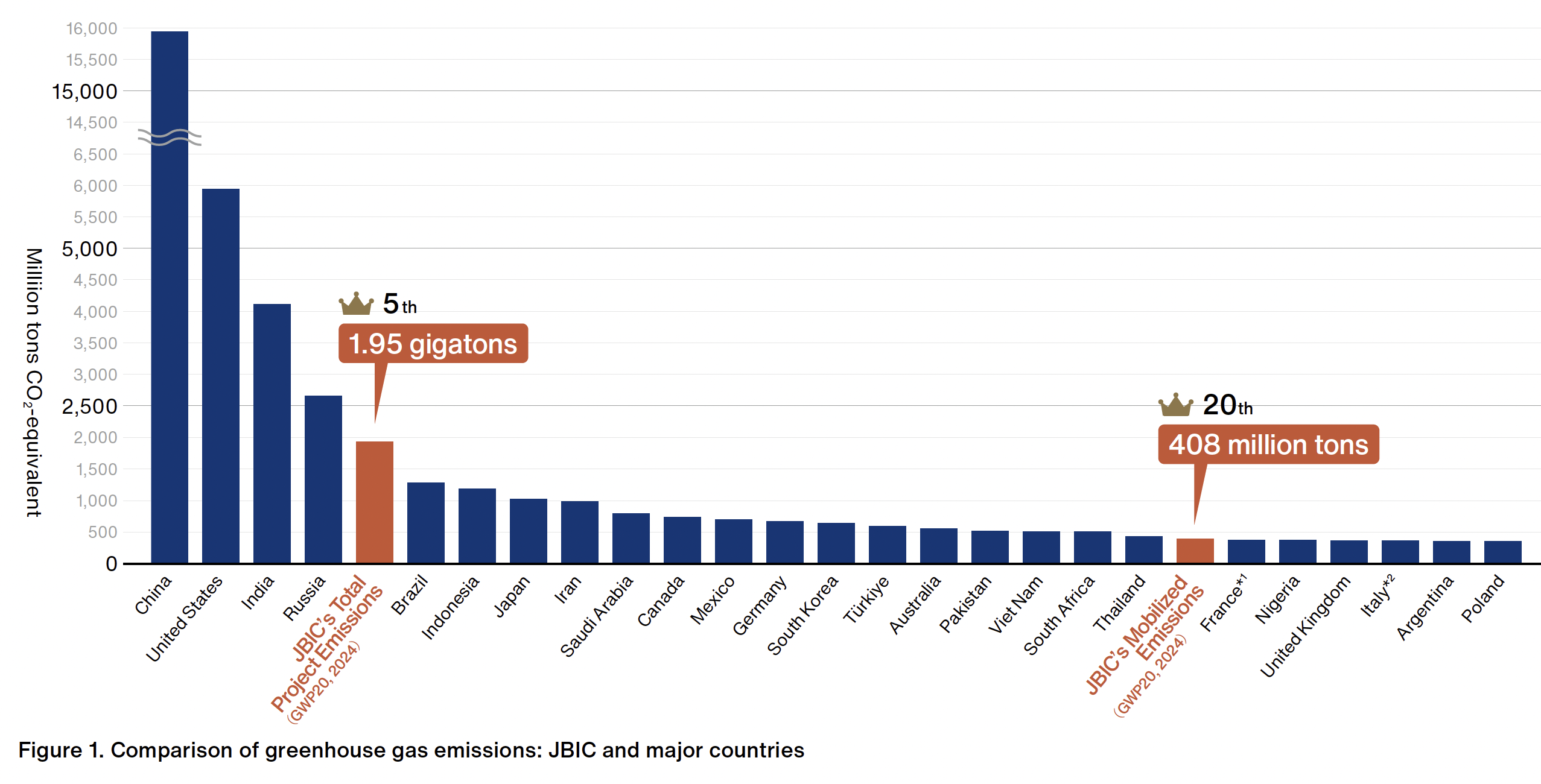

There is a serious blind spot in Japan’s climate policy: the vast greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions resulting from public finance for overseas fossil-fuel projects through the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and other government institutions. JBIC continues to provide large-scale loans and investments for fossil-fuel projects abroad, generating massive GHG emissions. Research commissioned by FoE Japan found that JBIC-attributable emissions in 2024 reached 408 million tons CO₂-equivalent (GWP20, mobilized emissions) in 2024.

If JBIC were treated as a country this would make it the 20th-largest emitter in the world, exceeding the annual emissions of many countries, including France, the United Kingdom, and Italy (Figure 1). Even if no new fossil-fuel finance were provided, JBIC’s existing fossil-fuel portfolio would still generate a cumulative 3.8 gigatons of CO2-equivalent between 2025 and 2050. If a remaining global carbon budget is 235 gigatons[3] from 2025 onward, JBIC alone would consume up to 1.6% of that budget. If humanity had only 100 steps left before breaching the 1.5°C threshold—the point beyond which the climate crisis becomes catastrophic—JBIC’s emissions alone would take one and a half of those steps. Such a level of emissions from a single public financial institution is indefensible.

Moreover, when considering all emissions from fossil-fuel projects financed by JBIC, the total annual emissions for 2024 reach 1.95 gigatons (GWP20)—which would rank JBIC fifth globally if it were a nation.

Underestimation of LNG and methane

Two factors explain why JBIC’s emissions are so vast yet often underestimated: first, the impact of liquefied natural gas (LNG), whose main component is methane; and second, the major role JBIC plays as an export credit agency (ECA).

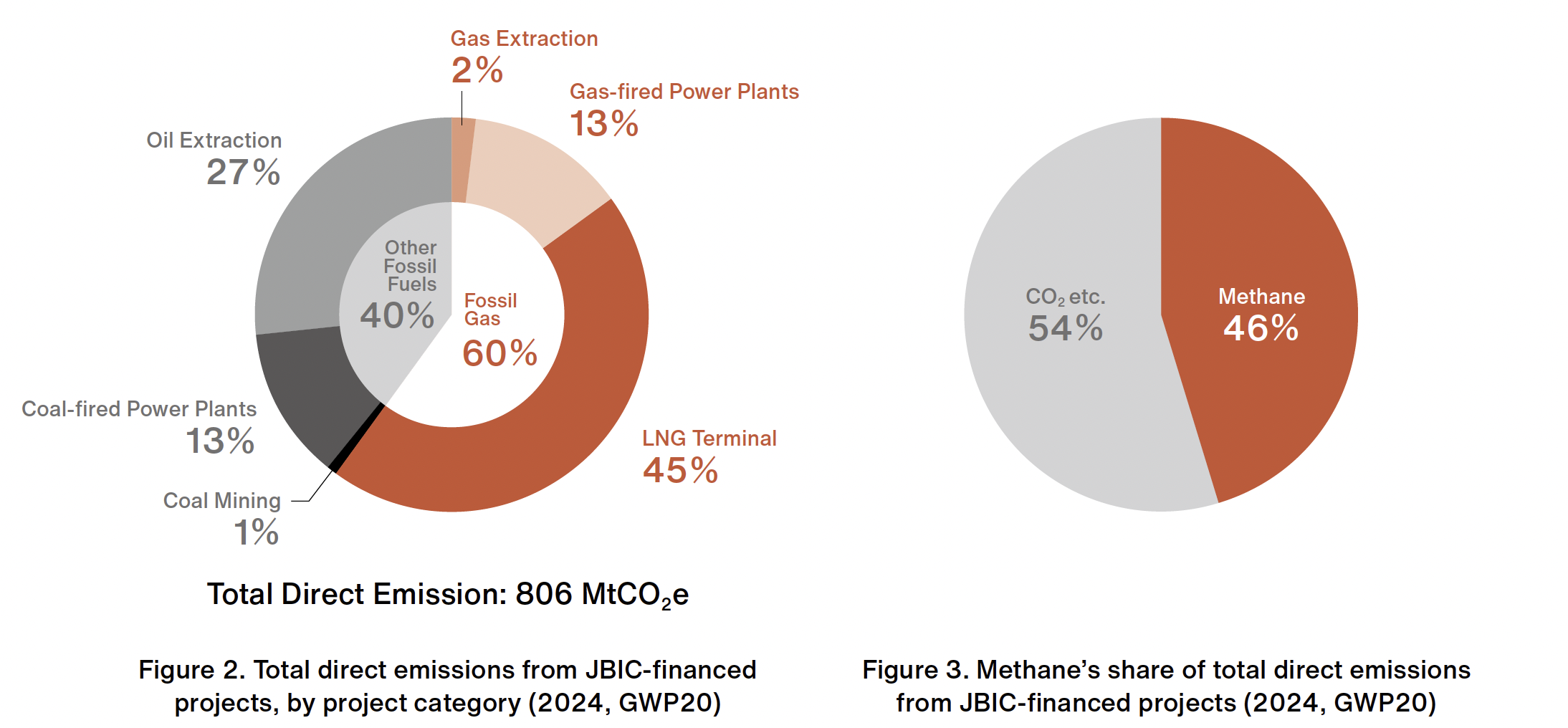

JBIC has actively financed LNG projects promoted as “clean” because they emit less CO2 during combustion than coal. As a result, gas-related projects accounted for about 60% of total direct emissions from

JBIC-financed fossil-fuel projects in 2024 (Figure 2).

Methane, the principal component of LNG, has an atmospheric lifetime of only about 12 years, but is an extremely potent greenhouse gas. Its Global Warming Potential (GWP) is 29.8 times stronger than CO2 over 100 years (GWP100) and 82.5 times stronger over 20 years (GWP20).[4]

Scientific research shows that assessing methane only on a 100-year basis conceals its massive near-term warming effect.[5] Given that the world could exceed 1.5°C (even when averaged over a 10-year period) within roughly six years at the current pace of emissions,[6] the next decade is decisive. Therefore, this study evaluates JBIC’s emissions using both (GWP20 and GWP100) to capture near-term climate impacts.

How much of a difference does this make? Under GWP 100, direct emissions (excluding indirect emissions) from JBIC-financed projects in 2024 amount to 566 million tons CO2-equivalent, but under GWP20 they reach 806 million tons. Clearly, the use of GWP100 significantly underestimates the climate impacts of methane emissions from JBIC-financed projects during this critical decade. Methane accounts for 46% of these emissions under GWP20. In other words, ignoring methane would overlook almost half of JBIC’s true climate impact.

Underestimation of the role of export credit agencies

Public institutions such as JBIC, established to support national exports and secure strategic resources, are generally classified as export credit agencies (ECAs). In the fossil-fuel sector, ECAs play a decisive role in reducing commercial risk for private corporations. Projects in coal, oil, and gas are capital-intensive and long-term, making them too risky for private banks and investors alone. By providing financial support, ECAs like JBIC mobilize co-financing from private banking consortia and, in some cases, attach insurance or guarantees to private loans—significantly lowering private-sector risk.

Without such public finance to leverage private capital, many fossil-fuel projects would not proceed at all. As standout cases, Sakhalin II LNG (Russia), the Quang Ninh Coal Mines (Vietnam), and the Hail Oil Field (United Arab Emirates) each have JBIC’s direct lending exceeding 60% of total project value (debt plus equity), and the financing share reaches 100% when cofinancing mobilized alongside JBIC is included—meaning the projects’ funding requirements were fully covered by JBIC and the capital it mobilized. In addition, projects such as Cirebon 2 Coal-Fired Power Plant (Indonesia), the Central Java (Batang) Coal-Fired Power Plant (Indonesia), and the Safi Coal-Fired Power Plant (Morocco) show JBIC’s direct lending at or above 30%, rising to approaching 80% when cofinancing is included. Across the portfolio, this pattern demonstrates how indispensable JBIC’s role has been in enabling fossil development.

Therefore, when calculating JBIC’s “financed emissions”—the GHG emissions associated with its lending and investment activities—it is essential to recognize JBIC’s catalytic role as an ECA. In particular, when determining what portion of a project’s total emissions should be attributed to JBIC, the magnitude of its influence must not be underestimated. To attribute GHG emissions to JBIC’s financing activities, three calculation methods can be considered:

1. Total Project Emissions — The total GHG emissions generated by the projects which JBIC provides loans or invests in.

2. Mobilized Emissions — The portion of total project emissions corresponding to the combined share of project financing mobilized by JBIC, including co-financing with private banks, as a share of total project costs.

3. Direct (Standalone) Financed Emissions — The portion of total project emissions corresponding to JBIC’s own direct financing share of total project costs.

In standard financial-sector accounting, financed emissions are often assessed only through Method 3. However, for an ECA like JBIC, relying only on this approach would underestimate its role in mobilizing additional private finance. Calculations of JBIC’s financed emissions should therefore, at a minimum, include Method 2 (mobilized emissions) to reflect its true leverage and responsibility.

Inconsistency with the Paris Agreement 1.5°C goal

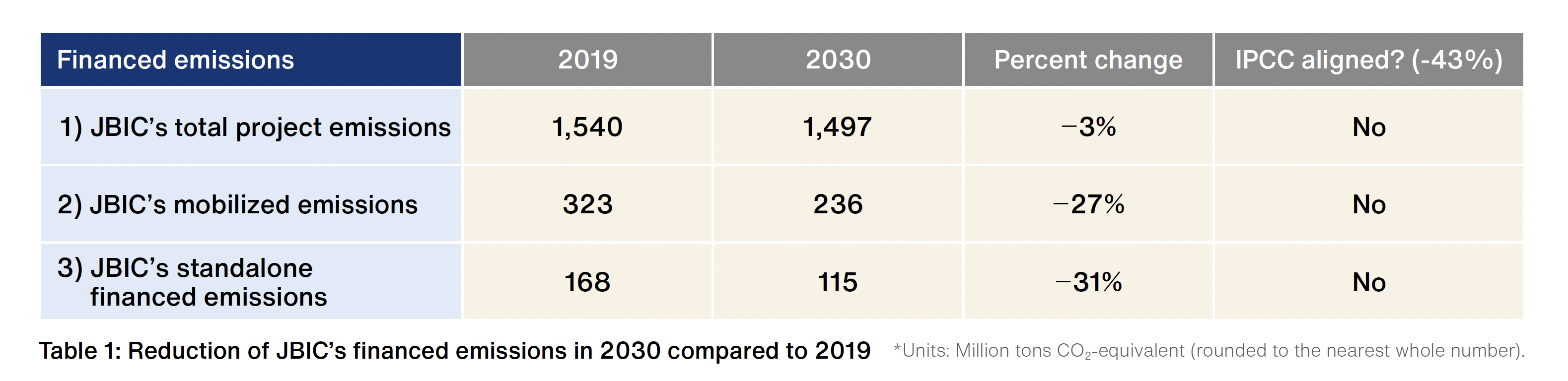

The Paris Agreement, which entered into force in 2016, sets the objective of limiting the rise in global average temperature to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Achieving this goal requires reaching net-zero GHG emissions by 2050 and making substantial, steady reductions by 2030 as an interim milestone. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), global GHG emissions must decline by around 43% from 2019 levels by 2030 to keep the 1.5°C target within reach. However, this 43% reduction represents the global average. Taking into account historical responsibility and equity, developed countries such as Japan—and public institutions like JBIC—must achieve deeper cuts.

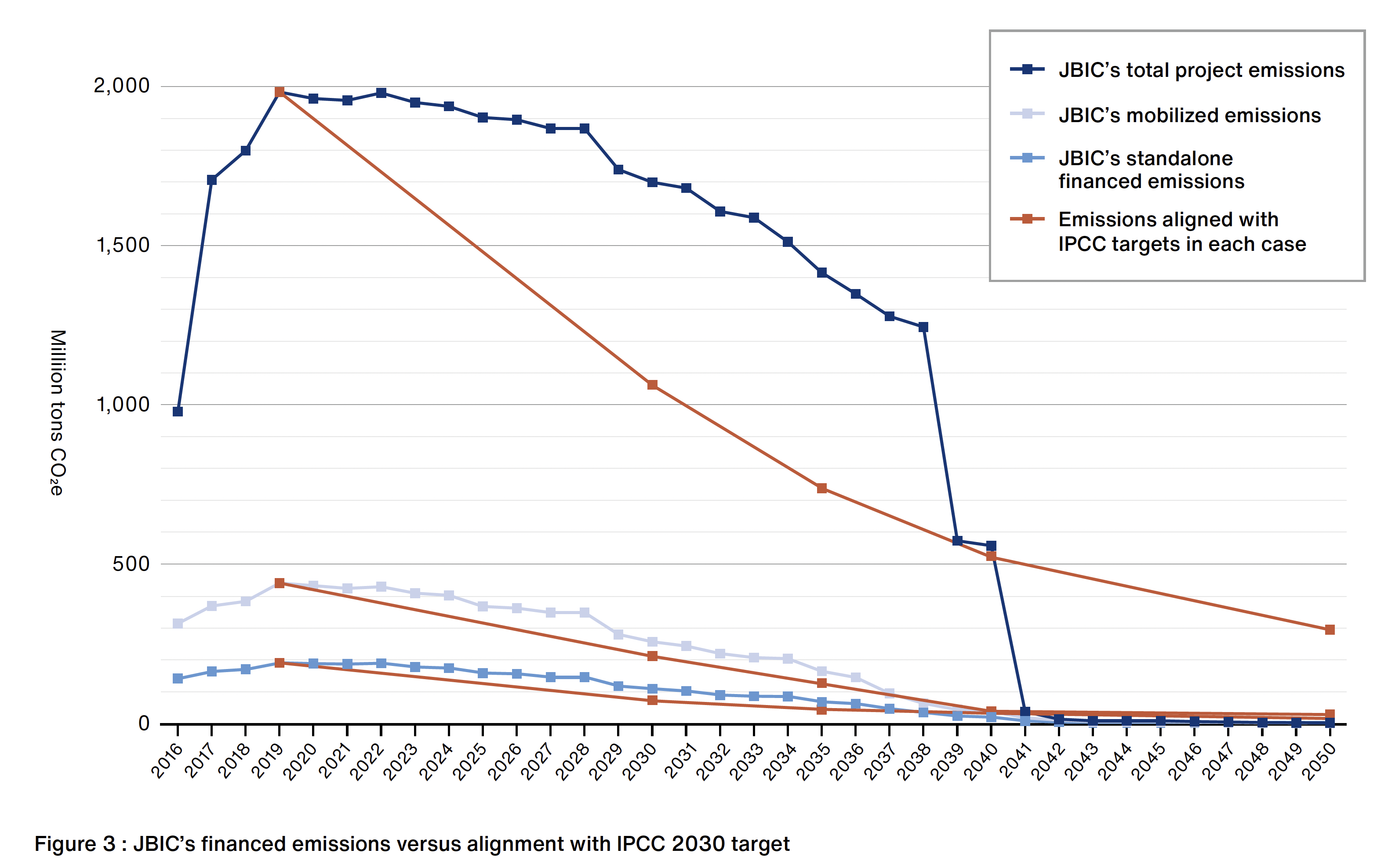

Analysis of JBIC’s annual GHG emissions shows that, under all three attribution methods described earlier, JBIC’s emissions trajectory is not aligned with the IPCC-recommended reduction rate. Compared with 2019 levels, projected reductions in 2030 amount to only 3% for total project emissions, 27% for JBIC’s mobilized financed emissions, and 31% for JBIC’s direct financed emissions—all falling short of the 43% reduction required (Figure 3). These figures already assume that JBIC provides no new financing for fossil-fuel projects after 2025. If JBIC continues to fund fossil-fuel activities beyond that point, its emissions trajectory will diverge even further from the pathway consistent with limiting warming to 1.5°C under the Paris Agreement.

Recommendations

Government of Japan and JBIC

1. End all new financing for fossil-fuel gas projects — with no exceptions.

The enormous GHG emissions resulting from JBIC’s financing activities are exacerbating climate change. Even if it provides no new financing for fossil-fuel projects, JBIC’s financed emissions are already inconsistent with the level of reductions required to be in alignment with the IPCC’s 2030 targets. Moreover, despite the Japanese government’s commitment at the G7 Summit in 2022 to “end new direct public support for the international unabated fossil-fuel energy sector by the end of 2022, except in limited circumstances clearly defined by each country consistent with a 1.5°C warming limit and the goals of the Paris Agreement,” JBIC continued in 2024 and 2025 to use an expanded interpretation of “limited circumstances” by approving loans for new fossil-fuel projects, including in Australia, Mexico and Vietnam. JBIC should immediately end financial support for new fossil gas projects, with no exceptions.

2. Disclose all GHG emissions, including financed emissions, and set clear 2030 reduction targets.

Starting with the fiscal year ending March 31, 2027, companies listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange’s Prime Market with a market capitalization of 3 trillion yen or more will be required to disclose GHG emissions across their entire supply chain. However, JBIC does not disclose the financed emissions from its investment and lending activities. Meanwhile, ECAs in countries such as the United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Finland and Sweden do disclose financed emissions in their GHG reports, while those in the United Kingdom, Finland, Denmark and others have also set medium-term targets. JBIC, which continues to drive massive GHG emissions through public financing of fossil fuels, must act as a responsible public institution by disclosing comprehensive information and disclosing medium-term emission-reduction targets consistent with the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement, which Japan has ratified.

3. Join international initiatives such as NZECA and the Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP), and lead stronger climate action within the OECD.

The Japanese government and JBIC have also refrained from participating in international initiatives among ECAs addressing climate change. Established in 2023, the Net-Zero Export Credit Agencies Alliance (NZECA) and the Clean Energy Transition Partnership (CETP) have committed to ending fossil-fuel finance and to disclosing emissions and reduction targets, as noted above. JBIC should join these initiatives to strengthen its policies on climate change. Japan should also use its position in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) to promote stronger rules on fossil-fuel finance and to engage fossil companies in setting and disclosing ambitious climate targets and emissions from their projects.

Institutional investors

JBIC raises part of its operational funding through the issuance of government-guaranteed bonds, which attract investment from domestic and international institutional investors. However, in line with the Paris Agreement’s 1.5°C goal, institutional investors should avoid purchasing bonds that directly or indirectly contribute to financing fossil-fuel projects. The substantial GHG emissions attributable to JBIC, as revealed in the study above, underscore the responsibility of investors who provide capital through these bond purchases.

Under the GHG Protocol—the globally-recognized standard for GHG accounting—when emissions from a financial institution’s activities (Scope 3, Category 15) are significant relative to other sources, such as in the case of JBIC, those emissions should also be included in the Scope 3 inventories of institutions holding that entity’s bonds.[26] Therefore, the large volume of emissions linked to JBIC’s financial activities should be counted by its bondholders as part of their own portfolio-level financed emissions, and investors should actively engage JBIC to promote credible emission-reduction targets and a phase-out of fossil-fuel finance. f