Submission for the United Nations Secretary General Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals

In May 2024, the Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals (CETM) was convened as an organization under the direct control of the Secretary-General of the United Nations. The mission of the panel was to consider not only the securing and stable supply of CETMs, but also preventive measures for environmental and human rights issues related to the supply chain.

In response to this panel, Friends of the Earth Japan (FoE Japan) , together with the the Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC) which has been conducting joint research on mineral supply chains, submitted recommendations on the right of communities potentially affected by mining to say no to mining projects and the necessity to ensure “Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC).

The original recommendation is in English as below (a Japanese translation is available here).

Recommendation for The UN Secretary-General’s Panel on Critical Energy Transition Minerals (CETMs)

We, Friends of the Earth Japan (FoE Japan) and the Pacific Asia Resource Center (PARC), firmly believe communities potentially affected by CETM mining have the right to say no to mining projects, and that those rights must be respected through a strong emphasis articulated in considering “Sustainable, responsible and just value chains”.

FoE Japan and PARC are members of the Japanese civil society with experience in documenting human rights violations and environmental destruction by Japanese enterprises in the Global South, offering technical support for local communities, assessing remedies and advocating for preventive policies. Through our decades of collective experience in the field, we would like to note the following.

Communities in the Village of Junin, Imbabura, Ecuador have faced threats of mining in their village for 30 years despite their repeated opposition to any mining in their territory. They have educated themselves on the potential harmful impacts to their lives and livelihoods, and collectively made that decision. However, the community faced continued pressure from mining companies through manipulation, threats of violence and actual violence by police and paramilitary agencies. The relentless pressure campaign altered community relationships in irreparable ways and fundamentally changed life in the village before any mining even took place. Even though the planned mine has been struck down by the courts and discontinued, the community has already suffered despite their clear and unwavering position to oppose the mining project.

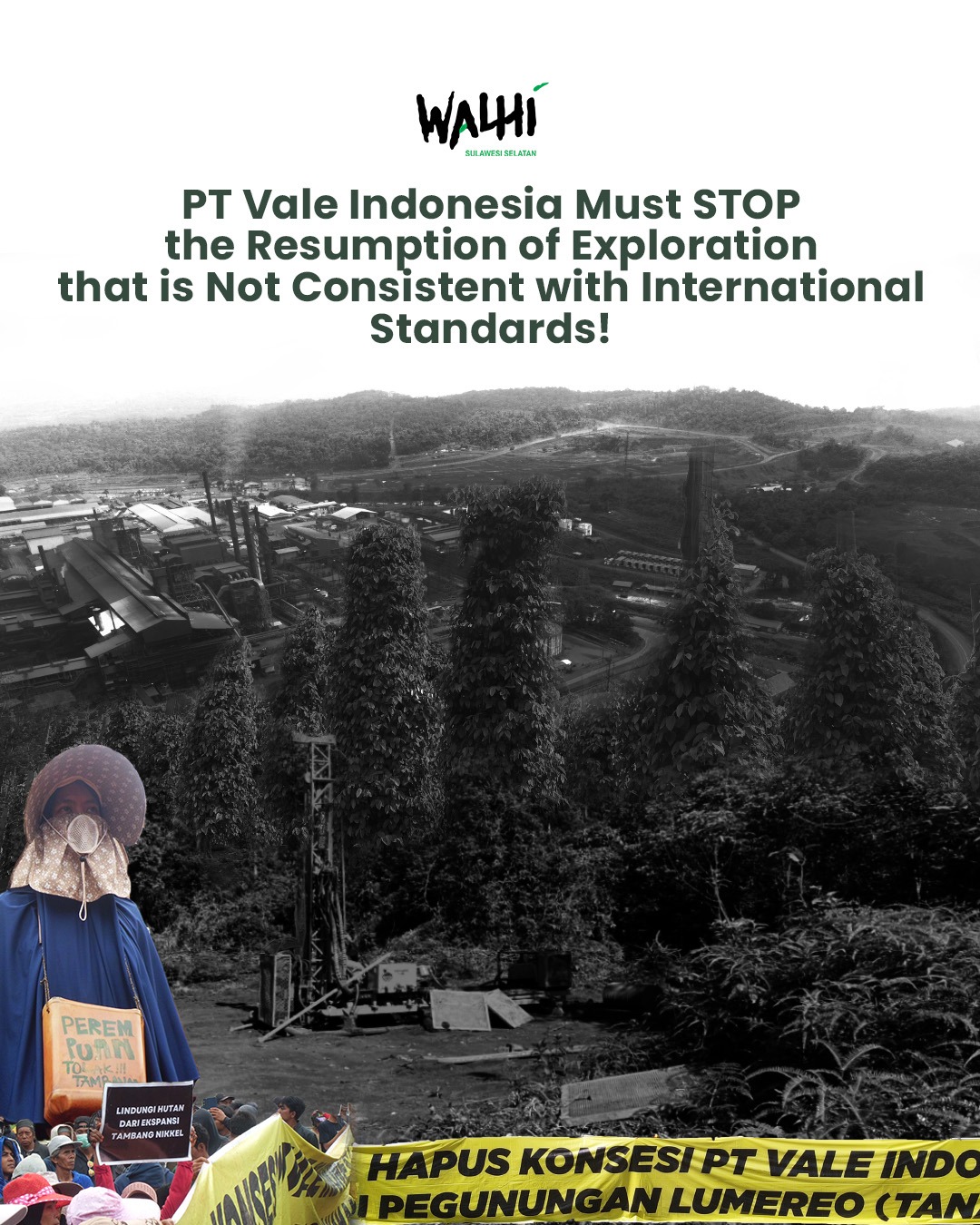

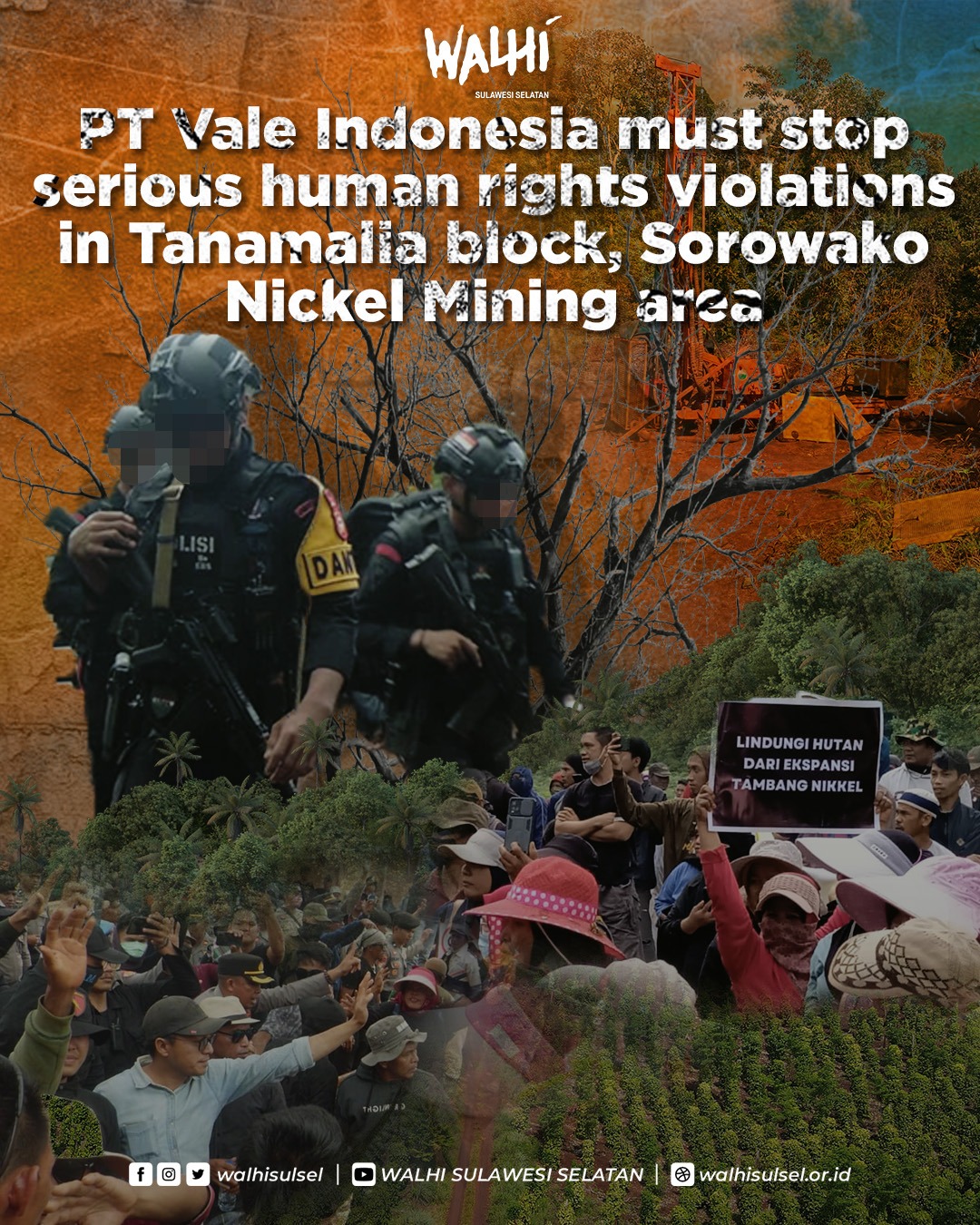

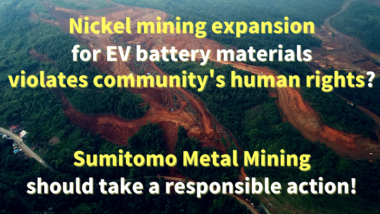

In a more recent example, villagers in Loeha, South Sulawesi, Indonesia, are now facing threats of mine expansion into their pepper fields, but the local farmers have been vocal in saying no to mine expansion in the farmland on which they have relied for their livelihood. However, the mining company men have been bringing in heavy equipment to move forward with the exploration right in the middle of the community’s farmland even without any notice or consultation in advance. This has already damaged some crops and post-harvest production during the exploration, created unnecessary conflicts within the community and keeps community members in constant threat and unrest. All this despite their clear and hard opposition to mining nickel in their territories.

Mining companies should not try to play the long game when it comes to mine affected communities. A prolonged struggle destroys intra community relationships and poses both physical and mental hardships to the community members that are clearly unwarranted. When a community expresses opposition to CETM mining, it should immediately be considered as their execution of their right to say no. Any manipulation from that point should be considered a violation of FPIC’s principles as well. In addition, global mining enterprises often vastly out resource rural and developing communities. Thus, a clear opposition from communities must be respected with a swift withdrawal of the project.

We also note that rights holders often hold those rights in customary means. Mining projects tend to take place in remote areas where land rights are not clearly defined or are not legally certified. When they are, they tend also to be contested territory inconsistent with customary uses. We thereby emphasize the importance of recognizing customary land rights when considering FPIC mandates.

While we acknowledge that the background paper of this panel considers demand reduction, mineral substitution and re-mining to be not sufficient, at least in the short term, in meeting the demands of the global demand for CETMs, we will stress that the consequences of such shortfalls should not be burdened by the communities who will be affected by CETM mining.

It is most likely the case that such communities have contributed the least to the climate crisis. It should first and foremost be the responsibility of the greatest emitters to bear the burden of the consequences of not being able to meet the global CETM demands.

This will of course not be politically favored in the Global North, and it may cause economic disruptions in economies that still currently depend heavily on fossil fuels. However, such economies have been warned for decades. Their slowness in responding to the climate crisis should not be overcome by sacrificing the will of potentially affected communities.

As acknowledged in the background paper, mining is a high-risk sector, and communities have a legitimate right to be concerned and to want to prevent mining on a precautionary principle.

We propose that this communities’ right to reject CETM mining be emphasized and acknowledged as a vital element of “Sustainable, responsible and just value chains”. We also propose that this right be fully acknowledged for customary land rights.

We would also like to see noted here that any attempts to manipulate communities through offerings of direct personal benefits, development of local infrastructure projects, jobs in the mining enterprise hinders community members from making decisions solely based on their free will and violates principles of Free Prior Informed Consent. Any excessively long efforts to manipulate communities is harmful by itself, and should be denounced as an infringement on the community’s right to say no.